During this month of Remembrance, thoughts turn to those who died in War. We know who they were, their names are on our memorials, some are buried in our churchyards, listed on plaques in churches, and elsewhere, but those who returned home, their lives changed forever, have remained anonymous. What was their experience and who were they?

Here are some of their stories.

Samuel Slaughter was 25 and living at Marlstaithe, Horstead when War broke out. He joined up early in 1915, and in September 1916, he was literally struck dumb. His medical record states, ‘Wound: shell shock, speechless and very nervous.’ He was transferred to hospital in Rouen. The following day he was evacuated by Hospital Ship to Shoreham-by-Sea where it was admitted that he had received no special treatment for his condition. Two months later he appeared before a medical board, where he complained of dizziness and general tremors. They concluded that as all his physical signs, heart, lungs, mobility, etc. were normal (presumably he could speak by now), therefore he was, ‘healthy but neurotic.’

Charles Riches, a railway porter who lived in Tunstead clearly suffered from some form of depression, which he attributed to a shell exploding near him, rendering him unconscious. He described his symptoms as being as if a dark cloud came over him making him feel unfit for work and inclined to wander. It lasted for two days at a time after which he felt perfectly normal. He was diagnosed as, ‘melancholic,’ but it was not considered a disability, although it was conceded that the condition was permanent. These cases are interesting because they illustrate the lack of understanding of psychiatric disorders in the early years of the 20th century. Medics then had no training in psychiatry. All that they could measure were physical signs of injury or illness. If they were absent, it was assumed nothing was wrong. Sometimes referred to as, ‘neurasthenia,’ the condition now recognised as PTSD affected an estimated 21,549 soldiers, but was usually classed as weakness, hysteria or even insanity. Slaughter was lucky, he did not end up in an asylum (many did) but seems to have returned to a normal life. Riches was allowed a disability pension of 50%, but only for 6 months.

Not many of those who had joined up from our villages escaped unscathed. Most suffered from various illnesses, and according to 1921 statistics the ratio of sick to wounded in total was 3.1:1 although in Africa it rose to a staggering 43.2:1. Leo John Harmer served in India but before the War lived in Anchor Street and had been an apprentice at Hunter’s boatyard. He must have been either one of the unluckiest or the unhealthiest, for between the years 1914 and 1920 in succession he suffered from: debility and bronchitis, appendicitis, pharyngitis, inflamed tonsils and syphilis. Many in all theatres of War suffered as a result of the conditions. Other diseases noted in the records were: scabies, impetigo, jaundice, bronchitis, nephritis and tachycardia (possibly stress induced). Surprisingly, I found no cases of trench foot or lice, but that may have been because they were too universal to add to a soldier’s medical notes.

A common illness amongst those who served in the Middle East or Africa, however, was malaria. In Mesopotamia it accounted for more deaths than enemy action. Albert Gurney, Arthur Gotts and Bertie Woodhouse (who had suffered nine attacks in as many months) had their pension claims dismissed on the grounds that malaria was due to climate, but John Haines and William Pettit were awarded 20% and 40% disability respectively. It is not known whether they continued to suffer attacks after the war.

Perhaps the most severely injured of those whose records were found was Robert Howlett, a butcher who although born in Coltishall was living in Wroxham when he joined up in October 1916. He received a gunshot wound (GSW) to his right thigh resulting in a compound fracture which completely shattered his femur. The problem with any such wound isn’t just the severity of the impact but the amount of debris the missile brings with it. In the early stages of the War, such a wound would invariably have been fatal, but by 1918 wound management had improved to such an extent that the survival rate was over 80%. Pte Howlett’s notes state that the debris was removed from his wound by counter incision and the use of Carrel tubes. The latter was a contraption consisting of several lengths of tubing connected to a rubber bladder, rather resembling an octopus, by which means the wound could be flushed out. By this time X-Rays were also in regular use and an X-Ray of Pte Howlett’s thigh bone showed how well the bone was healing. Left with the injured leg shorter than the other, he was nonetheless considered fit and only awarded a 20% pension.

By the beginning of 1916, it was clear the war was not going to end soon and so conscription was introduced. At first it only affected unmarried men between the ages of 18 – 41, but by May 1916, the law was amended to include married men and by 1918 the upper age limit was extended to 51 yrs. This would have included men like John Abel who was born in Coltishall and who had served with the Imperial Yeomanry in the Boer War. Many had volunteered in their 40s eg., Fred Child, George Rivett and John Barnard, who was aged 45 in 1915.

Conscription also captured the unsuitable, and among the extant records were several who were discharged unfit for service. Perhaps the most bizarre case found, was that of Pte Arthur Coman from St James, Coltishall. In July 1916, the medical board recorded that he was, ‘apparently normal but assumed great stupidity. Assumed deafness also. NOT DEAF. Flat feet.’ One month later, the recruiting medical board stated, ‘Totally deaf. Cannot hear words of command. Absolutely unfit for military service.’ It was countersigned: ‘Discharge recommended; totally unfit.’ Was he deaf or was he acting? If he wasn’t deaf, he was clearly a very good actor. We shall never know, but ironically having flat or deformed feet was in itself reason for discharge as they affected the soldier’s ability to march long distances. Three thus affected were David [Daniel?] Pye, William Buck and Harry Crane.

Those who were conscripted could, of course, make representation to a local tribunal for release. Some who were turned down, deserted with disastrous consequences. It was strange, then, to find a volunteer who became a deserter, but a former resident of Coltishall was one. He signed up from Gt Yarmouth in October 1914 and was posted to the Life Guards. After two instances of absenteeism on 29 March 1915 he had deserted and after an absence of 124 days, was apprehended by the civilian police. His punishment was 28 days’ detention. All his prior service was forfeited on trial by District Court Martial (DCM). In August he was discharged on account of his conduct, but surprisingly, was given a good character reference stating he was a ‘smart, intelligent man.’ Had his regiment been called up for service in the field he risked being executed, so what compelled him to desert? Unfortunately, as he also remained elusive on the census returns, we do not know what eventually happened to him.

At the other end of the scale was Carlton Watts. He enlisted on 8 May 1915 giving his occupation as farm labourer. He was discharged three months later when it was discovered that he was only 14 and a half years of age! He re-enlisted in March 1919 and was posted to Belfast. It seems that he was not destined to be a good soldier, for his record shows a litany of misdemeanours, most notably an inability to look after his kit. Perhaps he just needed to grow up a bit.

Online Sources:

Soldiers’ Service Records from the National Archives WO 96,97, 362 & 363. Obtainable from Find my Past and Ancestry

Census returns for 1911 and 1921 from Find my Past.

Other:

Corns, C & Hughes-Wilson, J. Blindfold and Alone, Chapter 7. ‘Shell Shock and the Great War’. (2001) Cassell, London.

Mitchell, T J & Smith G M History of the Great War Based on Official Documents: Medical Services, Casualties and Medical Statistics. (1931) Imperial War Museum and The Battery Press Inc. Nashville, USA.

Pictures:

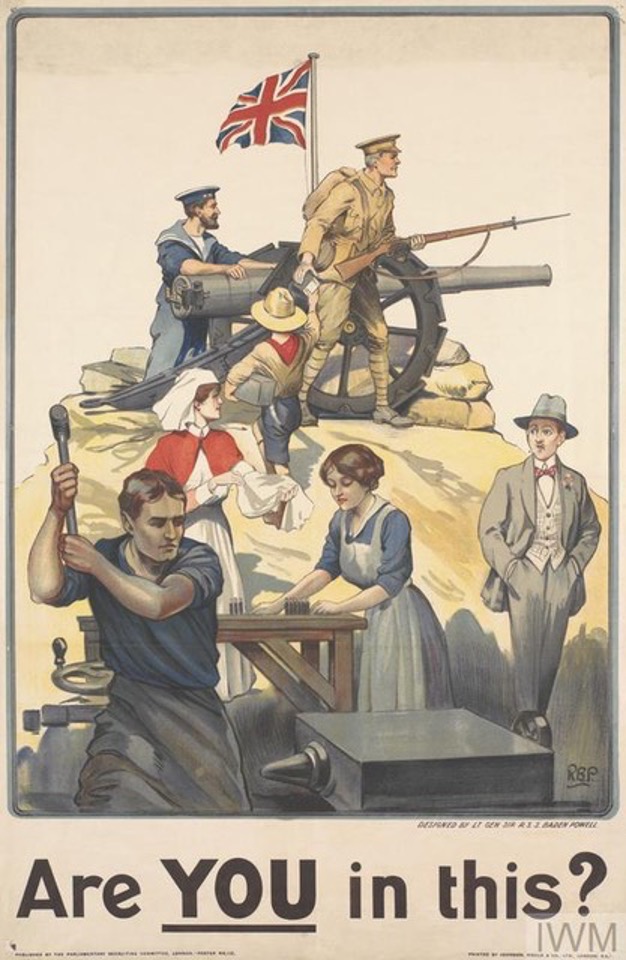

Figure 1: World War 1 Recruitment Poster. Source Imperial War Museum (IWM)

Figure 2: World War 1 Recruitment Poster: Source: IWM

Figure 3: Carrel Tubes for Steriising Wounds: Source IWM

| Campaign | Missing or POW | Wounded | Sick or Injured | Total | Ratio Wounded: Sick | |

| France & Flanders | 319824 | 1837633 | 3496688 | 5654145 | 1 | 2 |

| Italy | 344 | 4689 | 50552 | 55585 | 1 | 11 |

| Macedonia | 2778 | 16888 | 477518 | 497184 | 1 | 28 |

| Dardanelles | 7525 | 37193 | 497396 | 542114 | 1 | 13 |

| Egypt & Palestine | 3871 | 37193 | 497396 | 538460 | 1 | 13 |

| Mesopotamia | 15221 | 53697 | 803706 | 872624 | 1 | 15 |

| North Russia | 177 | 505 | 9461 | 10143 | 1 | 19 |

| East Africa | 1301 | 7777 | 330232 | 339310 | 1 | 42 |

| South West Africa | 782 | 560 | 24565 | 25907 | 1 | 44 |

| Total | 351823 | 1996135 | 6187514 | 8535472 | 1 | 3 |

Table 1:World War One Casualties (Excluding Deaths) 1914-1918. Adapted from data in Mitchel & Smith (1931)