Before the Roman came to Rye or out to Severn strode,

The rolling English drunkard made the rolling English road.

G K Chesterton (1874 – 1936)

There is little doubt that both humans and animals make tracks, so the history of Norfolk’s roads must go back to at least the earliest settlements which then were along river valleys suggesting that waterways were used for communication. If there were trackways, they must have been obliterated by the New Ice Age (10,000 BCE). By the neolithic period, however, the people of Norfolk were farmers and herdsman. There is evidence of the clearance of woodland for crops and flint mining. The population was becoming more widely distributed and the land would have been criss-crossed with tracks as goods were traded and animals herded. The existence of barrows further suggests that areas like the Holt-Cromer Ridge were well populated. Scatterings of pottery from the Iron Age, found in Norfolk also indicate widespread settlement. Some trackways remain today as sunken roads, but others are no longer visible.

Formal road building started with the arrival of the Romans, in about 43CE. Their construction was necessary for the transportation of goods and the movement of troops. There is no evidence for a road leading from Norwich to North Walsham, but there is for what is now the A140 running northwards from Scole. The nearest Roman road near Coltishall and Horstead for which there is evidence is that running from East to West through the Roman market town of Brampton, between Aylsham and North Walsham, which was a centre for the manufacture of pottery and of tanning.

In East Anglia, the Romans used gravel for the engineering of roads, but unfortunately gravel is easily ploughed up and destroyed, which may account for the lack of evidence of Roman road construction in the region. Probably the best-known surviving Roman Road is the Peddar’s Way – now demoted to a long-distance footpath! Another reason for the lack of Roman roads is the lack of need: conquering armies simply made use of existing tracks where possible. East Anglia was not greatly urbanised; apart from Venta Icenorum, the Roman capital just outside Norwich, the evidence of Roman occupation is mainly isolated villas and military sites such as the marching camp at Horstead.

After the Romans left in c4 little road building was undertaken until the c18. In the Anglo-Saxon era, Norwich was becoming an important market town with its own coinage. By Domesday (1085) it was the largest city in England with 25 churches and a population of between 5,000 to 10,000 and had a merchant community well established even before the Conquest. Merchants need to be able to travel to trade and it is surely no accident that Norwich is the centre of a road network radiating outwards like the spokes of a wheel.

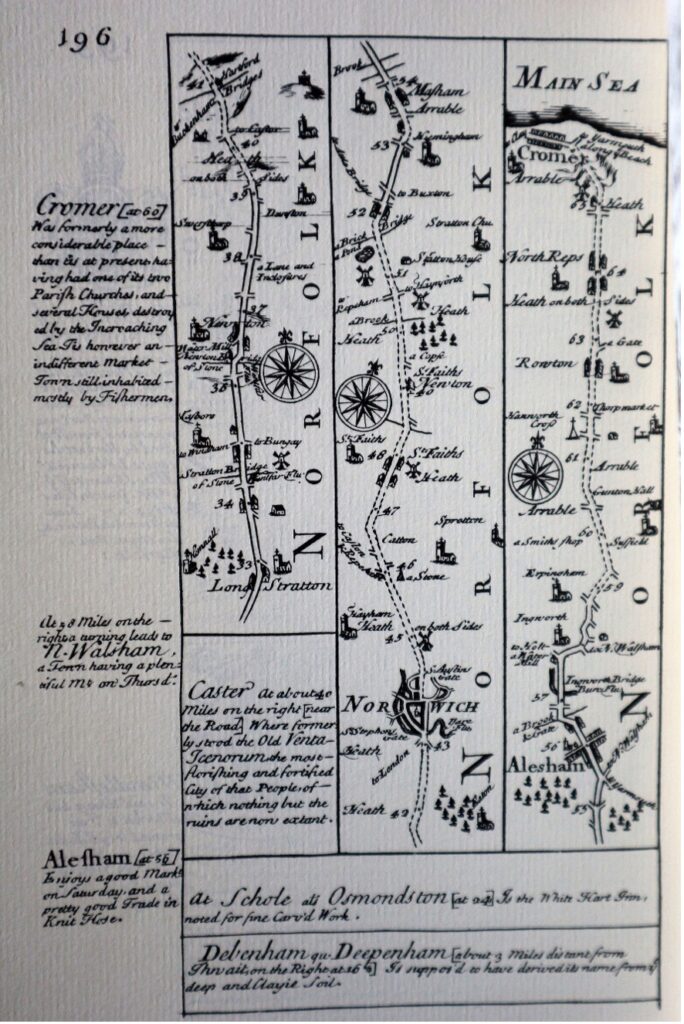

The growth of more minor towns and markets in the Middle Ages, largely, but not wholly thanks to the wool trade, meant a further rise in commerce. Scattered rural populations along the Bure and Wensum valleys needed to drive their livestock and goods to market which led to the creation of more substantial roads although they tended to happen rather than be a result of deliberate planning. The thirteenth century saw the building of bridges (Wroxham bridge dates from this time) and the emergence of pilgrim roads and wayside crosses. It is likely that the present North Walsham/Norwich Road (B1150) came into being as a pilgrim route to Broomholm, a Clunaic Priory (1113 -1536), near Bacton, which had a piece of the True Cross, reputedly able to perform miracles. Only the ruined gatehouse is now visible. It may account for why the 1845 Tithe Map shows a hermit cell near the junction of Frettenham Road and the Norwich Road. At around 1300 sea levels rose and it was about this time that the peat diggings flooded to form the Broads. With Cromer becoming the centre of the Icelandic fishing trade, it is no surprise the main road north from Norwich was to Cromer, not North Walsham, a situation which was to persist until at least the c19. John Ogilvy’s ‘Britannia’ (1670) shows the main road north from Norwich is towards Cromer, with North Walsham merely an offshoot.

The 1252 Statute of Winchester had a major impact on the creation of roads. It stated that highways connecting market towns should be widened and no cover provided for 200 ft on either side of the roadway. This was to deter an increasing number of thieves and footpads who were preying on travellers. Artificial causeways were also being constructed over marshland, and it is interesting to note that in the endpapers to Vol 1 of Margaret Bird’s ‘Mary Hardy and Her World,’ depicting life in the c18, the part of the Norwich Road which leads from the Recruiting Sergeant to Coltishall Bridge is called ‘The Causeway.’ The name persists in Causeway Drive and it is well known that the centre of Horstead has been liable to flooding, the worst case being in 1912 when the bridge was swept away.

Worstead and North Walsham had their first markets by the mid fourteenth century, although Tunstead (1260) and Mayton (1309) were earlier. By now North Walsham had developed into a town with the manufacture of fine woollen cloth its prime industry followed by agriculture. More markets meant more goods to transport and many of Norfolk’s major roads became recognised as ‘viae regiae’ or royal highways. This includes most of today’s A roads, although conversely many have now disappeared. The upkeep of roads was somewhat haphazard, relying on local parishes and bequests. For example, John Spendlove (1432) left in his will one Mark to ‘the Brigg [bridge] in Wroxham.’

From the c14, towns or parishes could apply to the King for the grant of Letters Patent to allow them to exact a toll, known as pavage, to pay for repairs to a road. Similar tolls were murage for the repair of town walls or pontage for the repair of bridges, for example the rebuilding of Wroxham bridge in 1576. Most of the responsibility for road repairs was undertaken by manorial courts and parish vestries, but during the Reformation, money from the sale of church plate and vestments was often used for road maintenance. Opinions of Norfolk’s roads at that time varied from ‘pretty deep’ (Celia Fiennes) to ‘better than in most other counties.’ (Nathaniel Kent).

At the beginning of the c17 a journey from Norwich to London took 4 days and by the Restoration of King Charles II the amount of road usage had necessitated changes. Norfolk became one of the first counties to experiment with road tolls. At Mayton Bridge, for example, there is a toll booth dating from the c15. Although in 1664 road rates had been introduced, a Highways Act of 1692 allowed the ratepayer to be charged 6d in the £ of income from real estate. Improvement of the main roads and the better design of vehicles meant that travelling times were becoming shorter. The early eighteenth century led to the need for further improvements, the rise of the short-lived Turnpike Trusts, and the great age of the stagecoach, more of which next time, as well as a glimpse of some c19 problems which are still all too familiar today.

Sources:

Barringer, C. A History of Norfolk. Carnegie. Lancaster. 2017 Bowen, E. (Ed) Britannia Depicta A Road Atlas of England and Wales 1720. (Facsimile Reprint 1970) Based on Ogilby, J. Britannia. C. 1675

Burke, T. Travel in England: From Pilgrim and Packhorse to Light Car and Plane. Batsford. London. 1942. Dymond, D. The Making of the English Landscape: The Norfolk Landscape. Hodder & Stoughton. London. 1985.

Fiennes, C. Through England on a Side Saddle in the Time of William and Mary. (c.1695) 1888 Facsimile Republished 2016. www. folkcustoms.co.uk.

Jones, A (Ed). Baskerville, T. Journeys in Industrious England. Hobnob Press. Gloucester. 2023 (Annotated Edition of Work c 1682).

Kent, N. A General View of the Agriculture of the County of Norfolk. London 1796.

Paterson,

Robinson, B & Rose E. Norfolk Origins 2: Roads and Tracks. Poppyland. 1983

Taylor, C. Roads and Tracks of Britain. J M Dent & Sons London. 1979.

Pictures:

Figure 1: A sunken road? Roman but not from Norfolk.

Figure 2: The Route to North Norfolk. Ogilby. Late c17. Note the margin comment about N Walsham. Source: J M Weightman

Fig 3: Detail showing Norfolk and Suffolk from the late c14 Gough Map. Note, North is on the left and both Norwich and Broomholm are shown with a connecting road. The map is named after Richard Gough (1705 -1809) who presented it to the Bodleian Library. The creator of the map is not known. Source: www,gough-map.uk.