Every Christmas Classic FM hosts a poll of the nation’s top 100 Christmas Carols. Consistently appearing in the top 5 is the carol, ‘O Holy Night,’ aka ‘O Night Divine’, but did you know that it is French in origin and relatively modern? Nevertheless. it has an interesting history which has taken it from France via Canada to America and the UK.

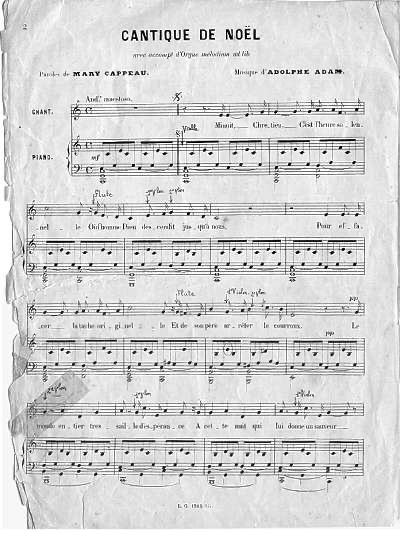

The story begins in the small town of Roquemaure in the wine-growing Garde département of the south of France, bordering on the River Rhône. It is 1843 and Abbé Maurice Gilles, Curé of the church of Saint-Jean-Baptiste wants to celebrate the installation of the church’s new windows.[i] He asks his friend, Roquemaure resident, poet and wine grower, Placide Cappeau (1808-1877), to write a suitable poem. Despite being an atheist, Cappeau obliged. It was thought so beautiful in its sentiment and apt for Christmastide that The Abbé was persuaded to have it set to music.

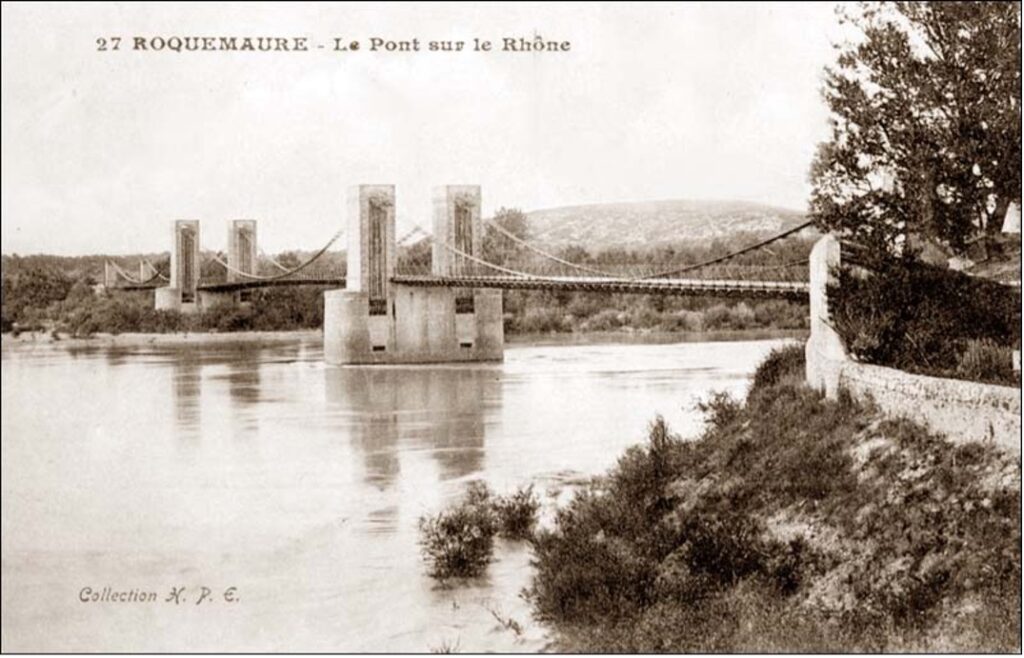

In one of those moments of serendipity that occur throughout history, it happened that repairs were being undertaken to the bridge over the Rhône at the time and the wife of the engineer in charge was a retired opera singer who was an acquaintance of Cappeau’s wife. She knew just the right person to set the poem to music: Adolphe Adam (1803 -1856) a well-known Parisien composer of various romantic operas and ballets.

In 1846 L’abbé Gilles died and was succeeded by L’abbé Petitjean who arranged for Le Canticle de Noël, as the carol was called, to be sung at the Christmas Mass in 1847. It had a mixed reception. The French Catholic Church banned it. Several reasons have been promulgated: it was too popular and had revolutionary sentiments; the poet was an atheist republican and a drunk; the composer was accused of being a Jew, although several sources dispute the fact; it preached equality whereas the Catholic Church and post-revolutionary France, still in a state of turmoil after the Napoleonic Wars, believed some were more equal than others. It was too saccharine and romantic. Most of all there was an objection to the line, ‘ Et de son Père arrêter le courroux’,[ii] as Christian doctrine did not believe in a wrathful God. To make matters worse, the composer dubbed it, ‘The Religious Marseillaise,’ which did not endear him to those who still longed for the ancien regime.

After that, Minuit Chrétiens seems to have taken up a life of its own. It was likened to the sentiments of ‘L’Internationale (1871); stories circulated that during the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71) the French soldiers sang it in the trenches on Christmas Eve, causing the Prussians to cease hostilities and respond with a carol in German. If that sounds familiar, it could well be that somehow it became mixed up with the similar story of the First World War football match. What is known is that French Canadian composer and musicologist Ernest Gagnon heard it whilst holidaying in France in 1858 and took it back to Québec. From there it crossed to the US where it was translated into English by a Unitarian minister from Maine, John Sullivan Dwight. It was inevitable that the abolitionist sentiments of the third verse, ‘Chains shall He break, for the slave is our brother…’ led to its being taken up by the Northern, abolitionist states in the American Civil War. It is interesting that the line. ’C’est pour nous tous qu’il naît, qu’il souffre et meurt’,[iii] in the third verse didn’t make it into English, however, being replace by ‘Let all within us praise His Holy Name’.

Whilst the Carol grew in popularity, French Catholic criticism continued well into the 20th century, accusations being made that it was, ‘hare-brained, facile and banal.’ Nevertheless it became increasingly popular, particularly amongst the American Civil rights movement, although the third verse with its abolitionist message was often omitted. Many artists have included it in their repertoire, including King’s College Cambridge Choir, Johny Mathis, Andrea Bocelli, Luciano Pavarotti, Placido Domingo, Josh Groban, Maria Carey, Céline Dion, and Susan Boyle. There is even an AI version of Freddie Mercury singing it, but I would give that one a miss.

When I hear ‘O Holy Night,’ on the radio I shall know that Christmas has truly arrived. May you all have a great Christmas holiday and a Happy and Prosperous New Year.

[i] Some sources say it was to celebrate the installation of a new organ, but this was completed some twenty years earlier.

[ii] ‘…And appease the wrath of his father.’

[iii] ‘It was for us all that he was born, suffered and died.’

Illustrations and Sources:

All illustrations are from Wikipedia unless otherwise stated.

Sources Online:

www.americanmagazine.org/arts-culture/2020/11/19/brief-history-o-holy-night-chirstmas-hymn-review

https:///sergecazelais.com/minuit-chretiens-un-chant- chretien/

Other:

Jones, Colin. The Cambridge Illustrated History of France. 1994. Cambridge University Press.

Fig 1:

Fig 2: The Bridge at Roquemaure

Hig 3: Placide Cappeau. Note the empty sleeve. Cappeau lost his right arm in a childhood accident,

Fig 4: Composer Adolphe Adam